Russell Davies

As disappointed as you are

About | Feed | Archive | Findings | This blog by email

« August 2008 | Main | October 2008 »

rediscovered

September 30, 2008 in diary | Permalink | TrackBack (0)

slow strategy

Warning - regular people might want to avoid this one. It's a rather pompous and oblique post about 'planning'.

One of the smartest things Richard ever said was that he didn't read all the books planners normally read, your Gladwells etc. 'There's no competitive advantage in it', he'd say. And he's completely right because planning isn't a body of knowledge to be absorbed, it's more like a act to be developed, like a comedian. You don't want to be doing the same jokes as everyone else. Even if you do them really well.

So, with the second IPA Fast Strategy conference happening tomorrow, and Fast Strategy starting to become an orthodoxy. Maybe it's time to examine the wisdom of all this speed. It's often good to be kicking against the orthodox.

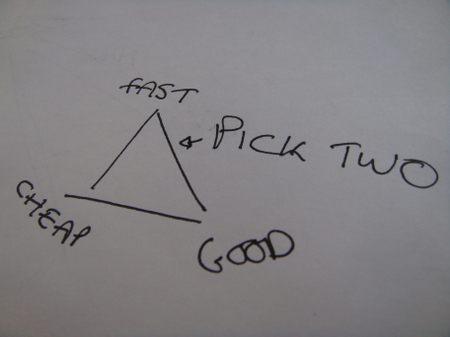

Firstly, whenever you hear mention of speed, it's worth remembering the eternal Project Triangle. That would suggest that if you're going to be quick then you're also going to either bad or expensive.

That might be worth worrying about. And does that seem true? Well, yes. A fast strategy is likely to explore fewer possibilities, will consider fewer contingencies. It will gravitate towards the obvious. This might work out well. But it is less likely to uncover the unexpectedly brilliant solution. Or the cheaper, less obvious one.

Secondly, going fast will tend to reduce the amount of collaboration you do. Fast strategy is perfectly possible, but it's best done in the head of a single person, or the heads of a really tight team. Not necessarily a bad thing. But not always the right thing. Sometimes strategy needs to be mulled over by an organisation. Nike used to describe it as 'socialising' an idea. It needs to be walked round the corridors, knocked around a bit in meetings, examined by different disciplines. Fast strategy might yield a big idea, but a slow strategy, a socialised strategy is maybe more likely to yield a rich one.

Thirdly, are we sure this isn't all just a cost-saving thing anyway? I'm convinced that planning was mostly invented because it was cheaper to have a planner thinking about something for half the process rather than having the creatives thinking about it the whole time. Are we sure that Fast Strategy isn't just a way of selling a process to a client as an innovation when it's really just a way to eat up less agency resources. Do Fast Strategies cost the client less?

Fourthly, and I know this is a bit tedious, it might be worth wondering whether we really want Fast Strategy or Fast Tactics. I'd argue that strategy should be a slow, evolving, socialised, collaborative, gradualist process. It should grow out of business decisions, the purpose, the values, the conversations of an organisation. Warren Buffett should be your strategy role-model. Tactics might be the place where speed is valuable. The smaller, more frequent, more granular manifestations of your strategy are when the risks of doing something expensive or bad are mitigated by the opportunity to do something timely and appropriate.

And maybe that's where advertising's tendency to elevate it's own importance is allowing me to poke these holes. Because planners don't really do strategy do we? We do tactics. And maybe admitting that will make it easier for us to do it well.

Fifthly, should we even be talking about stuff in this linear way anyway? Wouldn't the best way to do this stuff be to evolve your strategy slowly but punctuate it with regular, informative bits of execution?

Sixthly (?) we should acknowledge that this is all a bit silly anyway. It's just an excuse for a conference and a blog-post. We tend to advocate the processes that suit us personally. When I was in agency life I was all about the fast strategy. Loved it. Couldn't get enough. Because it meant that I could get stuff off my plate really quickly and get back to blogging and sleeping. Now I'm more responsible for delivering actual projects I like the idea of 'slow projects' because it helps to rationalise my failure to deliver. (And, should you wish, you can see video of me and Matt rationalising failure like crazy at the Do Lectures here.)

I guess the real answer, as always, is the shoddy compromise; make sure that you can think and do both quickly and slowly. And then work out which suits you and your circumstances more. Because doing strategy happily is probably more important than doing it quickly or slowly.

September 30, 2008 in slow projects | Permalink | TrackBack (0)

hobgoblin

The Albert Hall is one of those baroquely Victorian places. (If you can say that.) You know; ornate, elaborate, greebly. And most of the technology they've thrown in complements it; the acoustic clouds manage to look like Alice Through The Looking-Glass mushrooms, the light supports and cables like cobwebs. A bit. Anyway, it all seems to hang together. In a good bricabracy way.

And then, slap in the middle, is the BBC (Proms) logo. Modern, simple, clean. Nice and everything, but it doesn't really fit. I appreciate the need for consistency and standards. But surely, sometimes, context is more important than consistency. Sometimes it might be better to fit in than honour the three-ring corporate identity binder. I bet the Beeb have got a curly, old logo knocking about they could use instead. Maybe something like this. Ben's said something similar here; let's stop worrying about consistency and make more greebly contexts.

September 30, 2008 in ideas | Permalink | TrackBack (0)

patina

We were in a diner over the summer. One of those reconstructed ersatz fifties places with lots of old newspapers stuck on the wall. Except it had clearly been around for at least 20 years. The fittings were worn in the right places, the door had the right not-jammed-any-more feeling. The edges of things were worn smoothed by the passages of many arses. It was fake, but it was still somehow authentic. It had patina.

I've been slightly obsessed with patina since I started writing egg, bacon, chips and beans. I think it's the thing I like most about cafes. It's not the same as age or history or vintage. A horribly designed place can have lovely patina. Patina says a simple thing: people have been here. People have used this thing. Their traces can't be erased, and they're really hard to fake.

So that cafe may have been a fake classic but it had real patina, real people have been there.

The Star Wars universe has always been good with patina and wear. It's one of the things that made it look different. Now they've got a range of weapons that are promoted as 'with battle damage'. If you were a trendperson you'd be getting your Maslov's out right now and start looking at the teen market - they're buying experience not shininess.

Disney have a damn good try at faking patina in the real world. I adored the matt finishes and shading of Toon Town the first time we visited. They'd taken cartoon furniture and given it the appearance of a lived life. And you see extensions of this in malls all over the developed world. This 'scene' from Tarzan's Treehouse isn't that different from what Pottery Barn are selling.

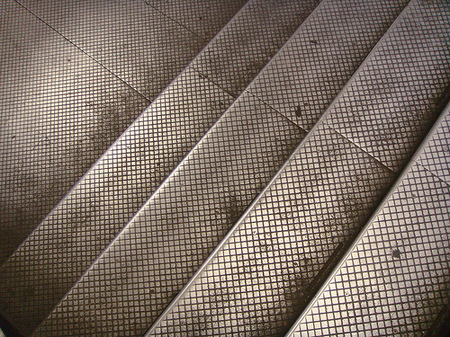

But patina is incredibly hard to fake. Which is why so much Steampunk stuff looks like Hallmark have started a new line of decorations called Christmas With A League of Extraordinary Gentlemen. You only get steps to look like this by having thousands of people tramp up and down them every day. I bet patina is something like Rudy Rucker's Gnarliness, something very complex generated from simple rules, but still so complex that the only way to simulate it is to completely reproduce it. You can only compute the gnarls of a tree with another tree. So the only convincing way to get yourself twenty years of patina is to hang around for twenty years. (Greebling will only get you so far.)

That's probably why luxury seems to be turning away from instant bling at the moment. The really rare and valued stuff can't be created or acquired quickly.

But you can pick materials that age well, show their patina gracefully. Formica being one. Leather. Wood. They show you that they've been used. And how. (And peeling paint seems to give you the aesthetic quite quickly.)

And then the back half of Matt's presentation from Picnic made me realise that I get the feeling of patina from some web things too.

Flickr, for instance, has the rub of patina about it. Flickr's full of people and they show you evidence of those people all the time. It feels worn into place by millions of clicks rather than imposed from above by a capricious design god. And it shows you your own usage, it moulds itself to you, so it gets as familiar as an old fountain pen. Sort of. Equally there are web places that more, well, wipe-clean - loads of people there but you never see any evidence of them.

Ah well. Anyway...

September 29, 2008 in ideas | Permalink | TrackBack (2)

the internet cupboard

I did this silly project a while ago. I made some physical tapes of various muxtape mixes. And, as is the way of these things, quite a few people never got in touch so I could send them their tape. (Or I forgot, which is more likely). So when I was reading this sad, thoughtful, intelligent piece about the death of muxtape (by its creator) I was staring at these physical incarnations of it. A pile of muxtapes.

It occurred to us later on on Friday that more of the internet could benefit from being preserved in this way. Wikipedia should be kept in a ring-binder, flickr should be in a shoe-box. Just in case. Haha. You know. Funny.

But I've not been able to get this idea out of my head. Maybe it's because I've been going through a bunch of stuff from storage recently but I like the idea of bumping into old physicalised bits of the internet in ten years, behind a sofa. Not a determined, rigourous, purposeful archive, but a haphazard collection accidental bits that you come across while living a life. Like collecting the bus tickets of the web. So I've got a ring-binder, I've written 'wikipedia' on it. I've stuck a print out of this in there. And I'm putting it in my internet cupboard. You wait, you'll all be coming round for a look at it soon.

(Incidentally, if you'd like your muxtape now, now it's a priceless historical artefact please drop me an email.)

September 28, 2008 in slow projects | Permalink | TrackBack (0)

blog all dog-eared pages: the percussionist's art

Most of this magnificent book went straight over my head, intellectually. But it still made excellent reading because sometimes reading someone talking about something you can't do is as exciting as watching them do it.

It's the enormous amount of thought that goes into Mr Schick's work that blows me away. Not just mechanical muscle-memory repetition and technique, but hard intellectual working-out. He seems to pour an incredible amount of attentional energy into each piece - as if he has to put enough Units Of Attention into the piece upfront that everyone who ever sees it will be able to drag enough attentional value out. Or something.

Anyway, on with the dog-earing:

page 5: "But what, finally, is percussion? Of course, we all know what percussion is. Percussion is that slightly dysfunctional family of struck sounds: a barroom brawl of noises, effects, and sonic events that can be created by striking, brushing, rubbing, whacking, or crashing any and practically every available object. The most succinct definition of percussion comes from German, Schlagzeug; Schlag means "hit" and Zeug means "stuff." We percussionists are musicians who hit stuff. It is the quality of the hitting and the nature of the stuff that effectively define the basic substance of our art and apply focus to the music we make."

I gave up German as soon as I could (more to do with the teacher than the language) but I always liked the lego-brick snap-together nature of it. And HitStuff is clearly the best definition of percussion. And it's the perfect opportunity to suggest that you visit Stefan's Neologist project - where he'll craft you a new lego house of compound German word - specifically to your order.

page 23: "Every early percussion piece was a mini-universe, a kind of percussive Noah's Ark featuring a representative spectrum of every possible kind of sound and performance skill, and the counterbalancing need to make sense of it all through a globalizing compositional scheme. The sheer number of instruments used in these early pieces was tiring. Often it takes longer to arrange the instruments for a piece like Luciano Berio's Circles (1960) then it takes to perform the piece. Every piece tried to do everything and ultimately the effect was numbing. In the movie The Blues Brothers, when Jake visits Elroy's apartment near the elevated trains in Chicago, he asks how often the trains pass by. The response, "so often you won't even notice," describes with equal accuracy the loss of sensitivity that attends musical saturation. Percussive color is easily exhausted as a musical commodity, and in the end the quest for plenty led to over stimulation and the concomitant absence of distinction. It became paralyzing."

Someone should start an Analogy Matching Service. Because often you find yourself with an image or an idea that you know is a perfect analogy for something, but you're not sure what yet. That instrumentally overstuffed percussion repertoire being refined into something clearer, emptier and simpler is obviously ripe with potential metaphoric meaning. Just not sure what for yet. I also love the way that he uses the Blues Borthers quote to illustrate such high-culture stuff. That's good writing.

page 79: "The realization that expertise in percussion playing might mean nothing more than the ability to cope with an endless supply of fresh dilemmas led me back to an essay written by Stephen Jay Gould. The relevant passage comes from his book Ever Since Darwin, and in it he claims that individual members of a species living at the edges of populations evolve more rapidly and radically than do individuals positioned closer to the centres of population. The notion is that the forces of nature are more brutal at the edges of a communal population; therefore they exact a greater need on the part of the individuals on the fringe to adapt. At the edge everything is rawer and less certain: space seems larger but poorly mapped, possibilities appear greater but are only vaguely defined. I could not stop myself from making the leap. In the community of musicians, were we percussionists necessarily more adaptable because we were living at the edge of the herd?"

Again; we have an Analogy Surplus here... "expertise in X might mean nothing more than the ability to cope with an endless supply of fresh dilemmas".

There are some great performance videos featuring Mr Schick on YouTube (which really is a universal arts festival), Some of them are that kind of intense, modern percussioning that you can imagine The Fast Show would have fun with, but I like them. Because I like the spirit of HitStuff, because there's clearly some meaning in there, even if I haven't figured it out yet. And because if you can't be pretentious on your blog, where can you?

September 19, 2008 in reading | Permalink | TrackBack (0)