Ben and Neil have posted their presentations from the Bucharest trip and I was feeling guilty that I'd not done the same. But I don't think just sticking up the powerpoint will be much help to people - it won't make a lot of sense on its own. And some of the stuff is sort of private (ie it was made while I worked for other people, and while I don't believe it's a problem to show it at a conference I think it'd be wrong to stick it online.)

So, what I thought I'd try and do is share and talk through most of the stuff here, in the hopes that some of the point will come over. This is, basically, my schtick, if you'd asked me to come and speak at a conference at any time in the last couple of years this is probably what I'd have done. I quite like presenting it, I've worked out where all the gags should go.

I've never written it down so I'm planning to just type it out as it comes into my head, it won't be that coherent. There will be typos and missing words and stuff but if I stop to think about it I'll never get it all down. That's one of the things I like about presenting, it can be more of a bundle of an ideas than an arguement. And you can make it up as you go along. Well, that's what I do anyway.

But now I've put it on here I think I need to get some more material.

I saw Tomlinson Holman present once at The School Of Sound and he started like this:

Just a blank screen, stood still, let it play. I thought it was magnificent. It just felt like something important or interesting was about to happen. I thought I'll start all my presentations like that from now on.

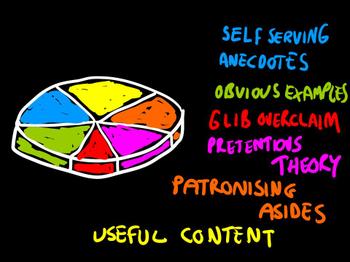

But first it's important to assert that this presentation will conform with the EU mandated thresholds established under recent regulations governing the scope and content of planning presentations. As above.

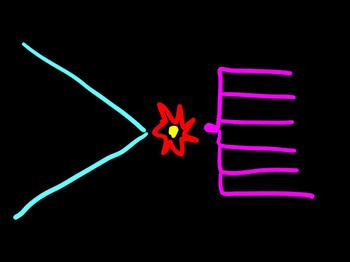

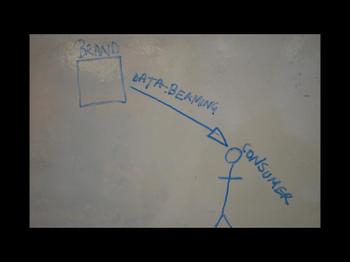

I was working for a large software manufacturer a few years ago and wondered into a meeting room after a marketing meeting. And this was drawn on the whiteboard. Either it was a proprietary technology they were working on, or it was a picture of how they thought communications worked. It wasn't how we thought communications worked, and fairly soon after that we ended up fired. But they more I thought about it the more the idea of 'how we think communications work' became important to me. And I spent quite a lot of time thinking about the models and metaphors we use to describe how advertising and marketing is actually supposed to work. Because I think many of us have very sophisticated and nuanced espoused theories about communications, but our theories in use are actually kind of simplistic and dumb.

That's the plan for this presentation today.

And we're going to examine the relative values of simplicity and complexity, strategy and execution and words and other stuff.

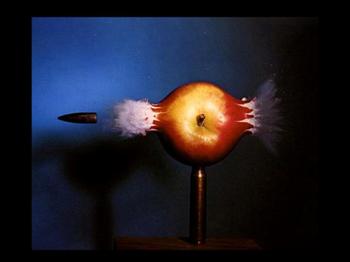

The first metaphor (or theory in use) to think about is the bullet to the brain. The message. The idea that the task of the planner (or whoever) is to distill the whole complicated range of what they want to communicate down to a tiny little nugget of message which 'media' will then fire into the consumers brain, causing some kind of 'change of mind'. When you express it like that it seems kind of stupid and I'm sure most people would say it's more complicated than that. But that's not how we behave, the whole industry is obsessed with the idea of a simple message, endlessly repeated.

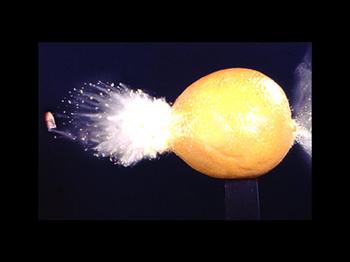

You don't see this picture so often do you? You see the bullet through the apple a lot. It makes an appealing metaphor. You don't see the bullet through the orange much because the bullet seems to tumble and emerge unpredictably. Maybe that's a better metaphor for what happens inside people's heads. But actually, there's even more slippery thinking behind the idea of the simple message, which takes us from bullets to tennis balls.

The first time a young planner comes up with a strategy or a creative brief with a little bit of complexity or a couple of parallel objectives in there some old git will normally say: ' listen young fellow/lady, if you throw one tennis ball at someone, they'll catch it. If you throw two they won't catch either.'

To start with, experimentally that's not true. Throw two tennis balls at people and they'll often catch one, sometimes two. But the theory in use behind the analogy is the more interesting thing here. It contains an assumption that consumers are just standing there waiting to catch the tennis balls that we're going to lob at them. Like this:

There's the consumer on the right, standing there, humbly waiting to catch the messages we lob at them. That's how most advertising people assume the world works. Have another look:

But of course the world isn't like that. Our consumers aren't sitting there waiting to have messages lobbed at them. The reality is more like this:

That's what the advertising process normally looks like. Our stuff is just bouncing off the back of people's heads. The best we can hope most ads will do is piss people off, maybe annoy them into paying attention.

This should not be news to anyone. 'People will only watch what they want to watch'. But it is news to many ad folk. Or at least, even if it's not news, it seems to contradict how we actually behave. And as regular people get more and more choice about what they do watch, they're choosing, more and more often, to not watch advertising. That's not really that surprising. What we normally build isn't designed to entertain or delight them. It's designed to change their mind. To get a bullet into their brain. Who wants that?

What people actually want is stuff with some complexity, some meat, some richness. Stuff that has depth, humour, tension, drama etc etc. Not stuff that's distlled to a simple essence or refined to a single compelling truth. No-one ever came out of a movie and said "I really liked that. It was really clear." Clarity is important to our research methodologies, not to our consumers.

Look, for example at this ad:

What would you say the 'message' of that ad is? No idea. Me neither. Because it doesn't really have one. But does that mean it doesn't communicate something of value? Of course not. I've got a little research video that show people watching that ad (which I won't put up here because the people in it didn't agree to that when it was made) and it shows what happens when they watch it. They smile. They move along with it. They nod. They move closer to the screen. And they say thankyou at the end. (How many ads do you get where people say thankyou for showing it to them?) Communication is going on here. But it's not verbal communication. It's communication with other bits of the brain. Mirror neurons are firing. All sorts of things are happening. But it's not about a single, clear message.

Maybe ads/brands/whatever work more like velcro than like a bullet or a tennis ball. It's not about one big, simple hook, but thousands of little ones. If some of them fail it doesn't matter. Some of them are verbal. many of them aren't. They're mostly the things that happen in execution, not in strategy. They're to do with tone, manner, character, attitude, look, feel. Orr to be more specific, they're to do with design, font, colour, photography, music, casting, copy, typesize. All that.

These are the things that really determine the efficacy of a piece of communication. Not the 'high-level message'. But we spend very little time thinking about them. We spend most of our time writing powerpoint and brand onions, arguing about the tiniest nuance of our strategies. Trying to decide whether the fifth word on our list of values be 'fun' or 'funny'.

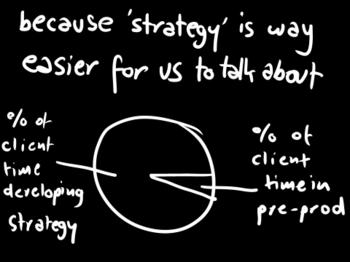

It seems clear to me that we do this, not because it's the right thing to do, but because it's way easier. We've got all sorts of great tools to talk about strategy. Charts. Graphs. Devices. Diagrams. And all kind of spurious new language as been created to do it. So we'll spend months agreeing the strategy and maybe an afternoon in the pre-production meeting, despite that probably being the most important meeting in the success of any piece of communication.

There is some dispute about who said this; Frank Zappa, Elvis Costello, Steve Martin or someone else, but I think it's the fundamental reason why we spend so much time arguing about strategy and so little talking about execution. It's because language is such a bad tool for the discussion of communications things like ads and websites. Business schools don't teach you how to talk about fonts or art direction, and even if they did, we'd only get to the obfuscatory language of art criticism. Which probably doesn't help.

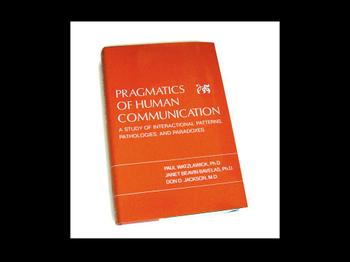

I saw Paul Feldwick talk about Watzlawick once and he explained it much better than I could. But the simple essence seems to be this. Human communication is divided between the digital (language, words, etc) and the analogic (tone, manner, body-language). Both are components of succesful communication. But we can't describe the digital using analogic language and vice versa. So if we confine the language of briefing and strategy to digital tools like words then we'll never be able to discuss at least 50% of what goes into our communications. Tone and manner statements on a creative brief will never do more than scrape the surface of what we're trying to get at.

(This seems to be more of problem than ever as marketing changes. Digital language is apparently mostly concerned with objects and the properties of objects, which always used to be the number one obsession of marketing - faster, cleaner, bigger, harder. But analogic language is more about relationships, and as marketing becomes more and more about relationships our inability to discuss the analogic is more and more of a hindrance.)

Big pause. Deep breath. Sip from a glass of water. Look around the audience.

So all those theories are all very well. What does this have to do with making ads. Good question. I'm not sure. But here's a story of some of the stuff we did on Honda which might explain some of it.

The pitch brief we got from Honda was one of the best client briefs I'd ever seen. The data made it very clear what the problem was - consideration. Once people started to think about buying a Honda they were quite likely to do it. The models, reviews, WOM were all great. The only problem is that it never really occured to people to think about a Honda in the first place. And the problem was that the brand was boring. Everything else was fine. It's just that Honda was boring. That's good. That's a problem that advertising can help with.

The second element of the brief was genius. They told us that they wanted to achieve very ambitious sales targets while reducing media spend every year. That was very smart. That demanded that we think about communications very differently. I loved that. Every client should do that.

Once we'd looked at the typical car marketing of the time it was obvious that out-thinking the opposition wouldn't be that difficult. Car marketing was in a stupendously bad phase. All the above ads are from a single issue of Top Gear magazine and they indicate the paucity of imagination in the business. If it hadn't been for the boffins at Nissan inventing a car that pointed the other way they'd all be completely identical. All we needed to do, to achieve some impact, was the opposite of what everyone else was doing.

And for the rest of the Honda story your best bet is to go here and download the APG paper. I basically say the same stuff but it's less rambly in the paper.

My basic point is that what we created on Honda was a way to do strategy and execution at the same time. The Book Of Dreams let us have all those analogic conversations about the brand, it let us talk about tone and voice and character and attitude and fonts and photography and colour. As part of the strategic process. And this helped us develop a brand that went beyond a few ads. Blah blah blah.

And then I get to this bit:

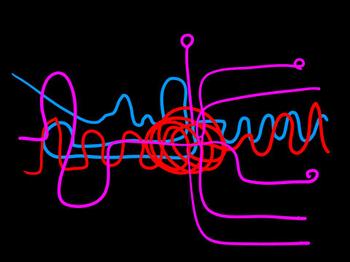

This is the model of idea creation that most agencies (advertising, digital, whatever) sell their clients. A bunch of smart strategists narrow down the strategic possiblities (with their clients or without) getting to a simple, smart, sharp, focused strategic idea which forms the basis of a controlled explostion of creativity. (Not too big, not too small). This idea is then implemented across a number of media channels to the happiness of everyone . This model is, of course, complete bollocks, and it's designed chiefly, to save money by a) keeping the really expensive people (the creatives) working for the minimum amount of time and b) making the process look calm and predictable. No good idea has ever happened like this.

The reality of any good process that produces great work is more like this:

It's a mess. A good strategist involves the executers as soon and as often as possible. She allows execution to feedback into strategy and vice versa. Something that happens at the end changes something you thought of at the beginning. It's chaotic, wasteful and unpredicatble. It involves lots of people, lots of dead-ends and wastes lots of ideas. But it's the only way to produce stuff that goes beyond the everyday run of communications. Something that people actually want to engage with. Something that works.

I never really know how to finish. I just peter out. Very bad. Oh well.

Hope this makes some kind of sense. Now I've written it down I'm not sure. Maybe I should film myself doing it sometime, maybe that'll be better.